review to come

Category: USA

The Body Keeps the Score (Bessel van der Kolk, 2014)

Bessel van de Kolk once received a request to help me find an internship. Or at least, that’s what I was told. No internship came of it, in the end. This was around 2014, and I guess one reason for not responding was that he was busy finishing this book – which bears the title of his pathbreaking article on his trauma research from 1996. What happened to the term trauma between those years to bring it in to such prime focus? Initially, van der Kolk pursued the field because of his own sense of traumatization during the WW2, as a boy in occupied Amsterdam. Later, as a young MD in the US, he began observing Vietnam veterans and their inability to recover from wartime experiences. van der Kolk outlines his own interest in the field in the beginning of the book, and his own story mirrors the evolution of the term from world wars to its current status as a word that has enjoyed exponentially increased dissemination the last ten years.

The book refers to a lot of studies of trauma, PTSD and dedicated a lot of pages to describing different modalities of treatment. He tells of CBT, EMDR, “bodywork” but also of drumming, theatre and song.

I recently partook in a four day course on a trauma treatment method called PE, where I asked the instructor what she thought about Bessel van der Kolk’s work. She scoffed at the mention of his book, which surprised me. My understanding was that he might be controversial, but still a respected authority on trauma. This proved to no longer be the case, at least for this particular instructor.

Later I found out that van der Kolk has been attacked by various journalists and writers for making the word trauma popular, and thereby twisting its meaning. It has become chic to refer to something awful that happened in the past as a trauma, and what once was only associated with the terrors of war, torture and assault now encompassed lighter problems like squabbles, neglect and other such slights. The death of a pet goes from being a sad event to being seen as an insurmountable emotional hurdle. This change has also fueled a movement that sees a system of generational trauma connected to historical racial injustice.

I am particularly invested in the idea of generational trauma since I am two generations down from holocaust victims, which is a fact that informs my self-identity (rightly or wrongly). My father’s life and upbringing was seriously stumped because of his parents had spent time in what is called concentration camps, a term I have a hard time with. His life informed my life. And my life informs my children’s lives.

My grandmother knew Bessel and used to attend his conferences. She even took to habitually carrying the little black and red bag from the conference as her usual carry-all. In big red letters on black background it said “TRAUMA STUDIES CONFERENCE”, which I guess gave her some kind of thrill to parade around with. She was herself a victim of trauma – and a wounded healer later helping other survivors.

Back to Bessel – he has recently also been accused of acting uncavalier at his workplace, which lead to his termination. This in addition to the claim that he has blurred the notion of trauma currently puts him in a somewhat disgraced position. One might say that van der Kolk has misshaped modern perceptions of trauma, but I believe that this tendency was evident in the zeitgeist regardless of his particular efforts. We are now in a moment where a countervailing force is emerging. This is represented by people who rather emphasise words like grit, resilience, robustness, and antifragility, to use a coinage by Nicholas Nassim Taleb. Another writer, Abigail Shrier, argues that “therapy culture” has made a whole generation into wimpy snowflakes, in her new book Bad Therapy. As usual, I think the truth lies somewhere in between these extremes. I took offense at reading Shrier’s ranty prose dismissing a lot of research findings. Sadly this is not unusual when a non-expert reviews psychological concepts. She pisses on epigenetics, on generationally inherited trauma research (conducted by Rachel Yehuda et al) on Bessel’s whole life’s work.

I am beginning to think there are two types of trauma researchers; those who’ve experienced trauma themselves and want to understand it, and those who want to make a career and happened to choose trauma as a specialty – and therefore don’t possess enough of an understanding of the phenomenon to really grasp what it is. I’m not arguing that one needs to suffer from the particular ailment one treats or does research on as a professional – that would be absurd – but I think in this particular case it might help.

Maybe You Should Talk to Someone (Lori Gottlieb, 2019)

A therapist memoir where we get to follow the therapist as practitioner, but also as a client in therapy herself – which is an unusual setup for this kind of book. The subtitle is “a therapist, her therapist and our lives revealed”. It seems to me that the book does a pretty good job of conveying the ins and outs of being a therapist. We also get a lot of backstory on Gottlieb’s career before becoming a therapist, which she seems to want to integrate in the story. She started in TV production, working on shows like E.R, then went to medical school, dropped out, started working in journalism. It was when she had some regrets about having dropped out of med school that someone suggested she might consider becoming a therapist. I know this because she tells the story in the book. She also tells the story of a few of her patients, and unlike other books of this kind, she includes precious vignettes that bring up various embarrassing or awkward moments that come with the job of a therapist. What happens when you bump into a client unexpectedly at the store? And what are the downsides of using Google to learn about your therapist’s private life? Interwoven is also the story of how she got pregnant, and the devastating breakup that leads her to seek out her own therapist. She tells us about her weekly collegial meetings where they discuss difficult current cases, and use insider slang about video sessions.

It is all very well crafted and it shows that Gottlieb is a writer, because even though some scenes come across as a bit unbelievable, she does a good job putting it all together; story, suspense, a bit of educative content about therapy all tied together with a human interest angle. Sometimes it’s a bit heavy on the fluff, but, hey, I guess that’s because it’s aiming for a large audience. It is very readable, and the chapters are just right in length for it to feel like you should read just one more.

All in all, a triumph of a book, which probably does a lot for spreading the gospel on the benefits of therapy. As a therapist, I found it pretty funny.

Comedy Book (Jesse David Fox, 2023)

Comedy book is a rare project, an updated nonfiction book about stand up comedy and its position in culture today. Most books on the topic are shticky novelty efforts, but this one takes its topic seriously – without being boring. In the vein of comedy nestor Kliph Nesteroff, culture critic Jesse David Fox has written a fine book on American comedy and how it relates to media, free speech, cancellations and our changing expectations on what should make us laugh.

It’s rare for me to read a book so filled with current events and topics that have been in the news. Mentions of many things from last five-ten years: covid, maga, woke, alt-right, BLM. A lot of the book takes up issues about identity politics, and analyses them through the lens of the comedy world. The book is structured around eleven chapters named for keywords: comedy, audience, funny, timing, politics, truth, laughter, the line, context, community, connection.

The age-old question: what is comedy? is adressed throughout, with theories and arguments about how our ideas about comedy have gone through many changes, and they continue to change, increasingly rapidly. One thread in the book picks up on the idea of post-comedy, where comedians do shows more or less without jokes. A typical example of that is a show called Nanette by Hannah Gadsby, which talks about abuse, or Tig Notaro’s show about her cancer. The comedy world is divided about it, one camp saying ”funny is funny” and the other holding on to ”it depends on the context” (which, post-Oct 7, is a complicated phrase). Fox is in the latter camp, and characterizes funny is funny-crowd as naive and closed off. I guess it takes a comedy critic to write a book like this, because no-one else would take comedy as seriously. Few people would make the effort to analyze comedy this rigorously, cause it’s hard to do without having the frog die (as the old E.B. White quote goes).

Reading this book makes me realize my generation is probably in a unique position with regards to comedy. Having been exposed to sitcoms since childhood, then seen the rise of internet humor and the establishment of a new comedy scene, largely spread through podcasts, we are familiar with a variety of comedy modalities, which someone who is a teenager today might not be.

One of the most interesting transitions in the comedy-sphere since the early 2000s is the rise of Jon Stewart and his role in the comedization of politics (or should it be the politicization of comedy? Probably both). Fox dedicated a chapter to this (and also has an extended riff on ”too soon”-jokes about 9/11). And now I hear that Jon Stewart is coming back to television, after his retirement six years ago.

Comedy is the the new ultimate frontier of what is allowed to say in our culture, as Stephen Metcalfe presciently observed in an article a decade ago). Granted, from George Carlin’s seven words to Joe Rogan’s incendiary podcast, comedians have always liked to push the boundaries, but with our increasingly polarized culture, there are plenty of new boundaries to push and a whole lot of new niche audiences there to listen.

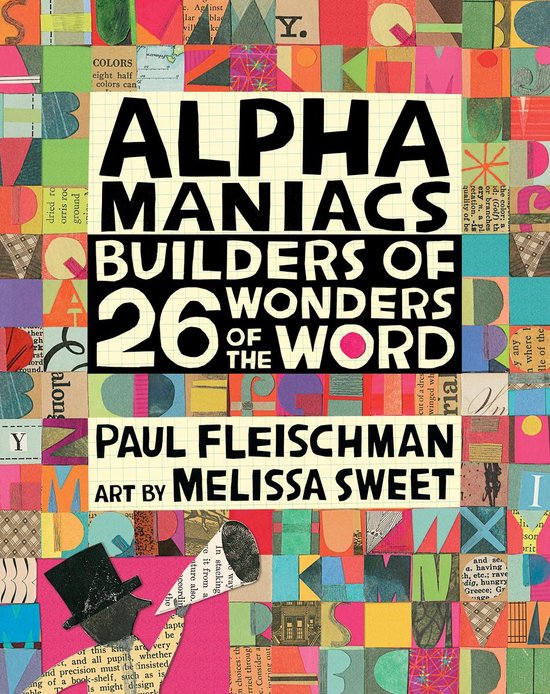

Alphamaniacs (Paul Fleischman, 2020)

Alphamaniacs is a fun book for all linguistically inclined readers! It is structured around 26 short bios of language innovators (why 26? One for every letter of the English alphabet). The selection spans from blink-writer Jean-Dominique Bauby to Ludvik Zamenhof, the founder of Esperanto. There is an emphasis on the playful, which is reflected in the tone of the writing, and also the choice of profiles. A bunch of the profiles are of artists who made typographical artworks, others are of hyperpolyglots, yet others who revel in art of inventing languages. But it is grounded in the alphabet. One chapter covers an American who transfers the Hebrew tradition of assigning numbers to letters, what s called Gematria, to English. Several of the areas have since long been niche interests of mine, but I’ve never seen them collected in a slim volume like this. Classics like universal languages, nonsense typography, experimental literature like Perec and Queneau. Other highlights include crossword wizards and the curious inventor of “PL8SPK”. I knew a lot of the material already, but it was still a joy to breeze through the book. Recommended for all language enthusiasts!

Arctic Dreams (Barry Lopez, 1986)

We who inhabit the northern parts of the world, should maybe make it our duty to visit the Arctic. We are its closest neighbors, yet I’ve met few countrymen who have taken the trip to the arctic regions. We may take it for granted, and consider it uninteresting or mundane. Which it most certainly is not – a fact that Barry Lopez‘ book Arctic Dreams very convincingly demonstrates.

Lopez is a naturalist, environmentalist, adventurer and essayist all rolled into one. He has written a nine chapter book about the Arctic region, based on his extensive research and wide travels. Each chapter centers around a theme, like Polar bears, Inuit culture, narwhals, monks, explorers.

Arctic Dreams is often mentioned as one of the greatest examples of “nature writing” there is. Barry Lopez, who wrote the book, is a fascinating person – an American environmentalist/adventurer who has traveled the Earth and chronicled the natural world, with a sort of dual perspective, both scientific and cultural. I was curious about what “nature writing” really referred to, which is why I was drawn to pick up this book. I have read stuff in the past that should qualify, like Peter Wohlleben‘s book about trees, or Annie Dillard‘s essays on nature. I’ve perused Thoreau’s Walden and noted names like Edward Way Teale, or Loren Eiseley as naturalists to read. I like the genre of travel writing a lot, which “nature writing” is closely related to, but where travel writing is a lot about moving in culture, nature writing is about moving in nature. Both are journeys, though, and the essayistic eye is common to both genres. Some books, like Redmond O’Hanlon‘s Trawler from 2003 where he recounts three weeks on a fish trawler from the Shetland Islands up to Greenland, are probably just as much travel writing as nature writing. Others get into this whole spiritual at-one-with-nature vibe, which seems to attract a lot of people. An example would be hiking alone for weeks through the Grand Canyon, as did Colin Fletcher and wrote a popular book about it in 1968. Man and nature, connection to the Earth. Something many of us feel we are lacking, and therefore might want to read about.

It goes back to Darwin’s journey on the Beagle, or the notes of Linneus and Humboldt. Lopez is quite classificatory, but he combines phylum and philosophy, and throws in a good measure of cultural history too. There probably are a number of factors which participants of nature writing score high or low on – and I could name a few. Scientific or impression-based? spiritual or materialist? environmental concerns or no? adventure or solitude/calm? Being in nature is a sort of religion, argues David Thurfjall, Swedish scholar of religiosity.

Reading about nature is, arguably, not as good as being in nature for real. But it can reveal different things than can firsthand experience. I sense there is something about our relationship to nature that is a bit off. And this may be slightly corrected by hiking, reading “nature writing” och the recent rebrand “forest bathing”.

Arctic Dreams reminds me of my time in Iceland (which is just about sub-arctic, though). It’s the closest Ive come to the arctic I think (barring a week in Lapland 2018). I learned a bit about inuits (some of whom who want to be called eskimos). They have an interesting term, a shaman-like role in their culture, which is called isumataq: “the person who creates the atmosphere in which wisdom reveals itself”.

The book contains many beautiful and interesting descriptions of natural phenomenon, like ice, snow, light and darkness.

“The evening I spoke with Haycock, I came across, in my notes about light, the words of a prisoner remembering life in solitary confinement. He wrote that the only light he experienced was “the vivid burst of brilliance” that came when he shut his eyes tight. That light, which came to him in a darkness that “was like being in ink” was “like fireworks”. He wrote, “my eyes hungered for light, for color…” You cannot look at Western painting, let alone the work of the luminists, without sensing that hunger. Western civilization, I think, longs for light as it longs for blessing, or for peace or God.”

Lopez makes a cogent argument that deep-rooted ideas about seasons, time, space, distance, and light are not applicable to the Arctic, and that different ways of thinking about these concepts are needed.

Emotional Inheritance (Galit Atlas, 2022)

Reading tales from therapy is a double-edged sword. The stories are so heavy, but at the same time they are strangely nourishing. There is something rewarding in taking in heavy stories. And this book does contain some devastating stories! There is a focus on sexuality, which I’m not really used to. I guess the Esther Perel-ness of it all feels very female. Several stories included instances of trying to heal hurt with sexuality. Female sexuality is probably more “weaponized” in the lifeworld of women, the vantage points are not equal when compared to men. Radical equality is probably not even possible because of the differences in sexual setup! Female perspectives are needed for men – and also vice versa.

Anyway, I’ve read a handful of books of ”tales from psychotherapy”, the first one being my grandmother’s dog-eared copy of Love’s Executioner by Irvin Yalom. I was fascinated by the vignettes of personal problems, the therapist’s view and then the unfolding of the process. I revisited the genre when I started undergoing therapist training myself, reading more. Stephen Grosz’s Examined Life was a compelling one. A family friend in New York sent me Robert Lindner’s Fifty Minute Hour, for a vintage taste (it was written in the 50’s). This time around I found Galit Atlas’ Emotional Inheritance, which focuses on intergenerational transmission of psychological trauma. There are eleven case stories divided into three parts, grandparents, parents and ourselves. I’m very interested in the generational view, which to me seems underdeveloped in psychotherapy. This book provided several good examples of this perspective, all drawn from Atlas’ own practice.

Throughout the book, Atlas is candid about her own thoughts and insecurities during the sessions, and she also opens up about her own complexes and traumas. In an interview she mentions that she considers her research to also be ”me-work”, meaning that her interest in trauma originates in her own traumatic experiences, which she processes as she helps others as well. This is the notion of the ”wounded healer”, common in folklore. She mentions the all-pervasive trauma machine that is the Israeli military (as Atlas is Israeli, she served in her youth). She also talks about the trauma of her parents’ families being forced to leave Iran and Syria during the period of persecution called Farhud. Another is her own experiences of relationships.

One of the stories in the book is the unbelievable account of a man who, although having grown up as an only child, senses that he had a twin brother who died and then discovers it to be true. What’s more, this phenomenon isn’t even that uncommon. Another memorable story is about a young woman whose family had been ripped apart when her grandmother accused the young girl’s (innocent) older stepbrother of abuse because of a sexual abuse trauma the grandmother experienced in her own youth. Such is the human comedy, tragic and flawed. I thought there would be more about the Shoah, but in a way it was better to keep it more universal. One fascinating point Atlas returns to is the fact that a lot of the patients activate a complex when they turn the same age as their parents, or when their children become the same age as they were when the had a defining experience. I wasn’t aware of how common this seems to be.

Interpreter of Maladies (Jhumpa Lahiri, 1999)

Jhumpa Lahiri is a London-born American of Indian extraction – now living in Italy and writing in Italian! This book was her breakthrough collection of short stories, and it came out before her mid-life move to Italy. It deals with Indian-Americans of various situations. Lahiri was 29 years old when this was published, so a lot of the stories are about relationships. I have become enamoured of the form of the short story and this was a fun way to try on a type of author that was new to me. I enjoy stories about immigrants who are straddling two worlds.

The book consists of nine stories, previously published in various publications. My favorites were The third and final continent, The Interpreter of maladies and A temporary matter. I saw that this book’s title got a very poor translation in several languages, where it is just called “the Indian interpreter” which misses the point so much it’s almost ridiculous. It is also strange to think that this was published 24 years ago.

Some of it seems to be a critique of arranged marriages, some of it a defense of them. One story deals specifically with views on religion and Indian identity in west (This blessed house). Lahiri is skilled at weeding out those poignant moments and sentiments that populate our lives which we don’t necessarily know how to express of explain. That is a real talent! It might be on the strength of this talent that the book was not only nominated but also subsequently the winner of the Pulitzer prize for fiction, which is a big deal.

The Island Within (Ludwig Lewisohn, 1928)

Ludwig Lewisohn wrote this 95 years ago. It amazes me, the will of instinct.

Lewisohn was from a very assimilated Jewish family that settled in the Midwest. His ”pintele yid” was small, on the verge of disappearing. You know when the embers after a fire are about to die out, extinguished from lack of fresh wood that would sustain the fire. Sometimes they grow a little just at the point of dying. This is what happened to Ludwig Lewisohn. Only he managed to make it grow.

He got ”reinvolved with his Judaic background” (a phrase I once heard composer Steve Reich utter in the Concert Hall of Stockholm when introducing his piece Tehillim) after a low-key antisemitic episode. Lewisohn was told by faculty that, because he was Jewish, he could never teach English at university. This led to an entire reorientation of priorities for him. He started writing on Jewish matters, became involved in the Zionist cause and wrote several books on the subject. This book is most likely inspired by his own life and thoughts. It tells the story of Arthur Levy (the very name a mini-conflict), a grandchild of highly assimilated German-Jewish immigrants who becomes a psychiatrist and who makes discoveries about himself in relation to the Jewishness and non-Jewishness of the world. This book struck a chord in me, because I harbor some of these thoughts too.

The book follows Arthur’s family history from Vilnius to mid 1800s Germany to America (the end also anticipates a trip back over the Atlantic to Romania). But what it ultimately is is an attempts to examine the place of American Jews in the 1920s. It deals with assimilation, internecine squabbles, mixed marriages, questions of heritage. It asks how one can approach and affirm the “island within”, which refers to the Jewish spark which Arthur tries to reignite.

I think I found out about Ludwig Lewisohn and this book through a list of reprints of lesser-known American Jewish writers. It offers an overview of American Jewish identity issues from a hundred years ago, which is quite fascinating. A lot of what Lewisohn writes about hasn’t changed a bit. It also differs from most Jewish novels of that period that has survived, because the majority of them come from a very working class, sometimes communist perspective and were written by first or second generation writers who came during the big wave of immigration (writers like Michael Gold, Anna Yezierska, Abraham Cahan, Henry Roth). Lewisohn has a different background, coming from this very assimilated background. He came up against the hydra of antisemitism which propelled him to rethink his place in the world and became a fervent defender of the Jewish people. The book also offers a panoply of issues that occupied Jewish Americans during the pre-depression 20s. For us 21st century people, aware of what would happen shortly thereafter, know that the perspective on the issues in this book would drastically change by the enormity of the Holocaust and its aftermath. Lewisohn is writing in 1928, and was unaware of what would happen 1939-1945, news of the NSDAP party was five years in the future at that point.

Most of the nine chapters are prefaced with a little essay on history, which is an interesting conceit. One is about the origins of Chanukkah, one is about Jews and civilization, another deals with technological change. It is a bildung-story beginning with Arthur’s grandparents and their story in Germany prior to coming to America. It gets to comment on a lot of ideas connected to Jewishness and the sociological position of Jewish people in non-Jewish milieux. I could very much connect to a lot of the things in the book, as I myself have thought about the topic of Jewish assimilation over the years. I think I’ve thought about it a lot in connection to being a way of coping with personal displacement, maybe primarily the most horrifying of displacements that is referred to by the name Shoah. Reading Lewisohn reminds me that of course many of those issues were and would have been there nonetheless.

One part that struck me as particularly interesting was the depiction of Arthur’s marriage and familyforging with Anne, the atheist daughter of a Christian preacher. It gave me insight into the difficulties of what is called a “mixed marriage”. There is an exchange in the book where Arthur repurposes Anne’s ironic Christian phrase “how will our son be saved?” but in the sense of saving his Jewish heritage.

The last chapter of the book involves Arthur reading the story of a horrible episode in Jewish history during the Medieval times where a mass suicide of a Jewish community took place because of persecution. Reading this account contributed to Arthur’s decision to further dedicate himself to helping the Jewish cause. The same Medieval episode is also described in detail in the book “The Last of the Just” by André Schwarz-Bart (1959) which I haven’t read, but I believe it shares some characteristics with this book, but updated to post-ww2 perspectives.

Leaving the Atocha Station (Ben Lerner, 2011)

Breakthrough book by the now fêted writer Benjamin Lerner. The story is an young unnamed writer on scholarship to Madrid where he spends his time avoiding to write, going to museums, and ingesting various drugs. The thing about Lerner is his artful prose and the observations. There is not much by way of plot. The end of the book involves a portrayal of the events of the Madrid Metro bombings of 2004, as seen by a 20-something American abroad. It’s a little bit cringeworthy, but most likely based on Lerner’s real experiences.

The book is full of poetry-like observations and prevarications, most of which are interesting. I have read Lerner’s books in the wrong order, so I started with the one called “11:14” which involves the Hurricane Sandy and the title refers to the exact time when a borough-wide blackout occurred in Manhattan. This means I recognized Lerner’s predilection for incorporating recent catastrophies or news events and giving them a literary treatment. Apart from that, it’s pretty straightforward autofiction. A lot of the story is about courting Teresa and Isabel, and their various travels to Toledo, Granada or the Madrid Hilton.

I could sympathize with the portrayal of what it’s like to be an exchange student in a foreign country. Language problems, certain “paralinguistic” forms of communication, cultural differences – it’s not always a smooth ride. All things said, Lerner is pretty good with words. Here is a representative sample:

When I awoke it was a little after three in the morning and I was perhaps hungrier than I had ever been. I’d been eating very little for two weeks, and the turn of my appetite, I assumed, represented a shift in my body’s relation to the white pills. I ate an entire two-day-old baguette and as I ate I checked my e-mail and there was a message in English from Teresa, who had only e-mailed me once or twice in the past, saying that she had heard I was back from “traveling with Isabel” and that she missed me.

or this weird drug-induced parataxis:

My mouth was dry and I poured myself a glass of white wine and said I didn’t care which poems I read but that I would only read one or two. Teresa said to read the one about seeing myself on the ground from the plane and in the plane from the ground and I said, in my first expression of frustration in Spanish, that the poem wasn’t about that, that poems aren’t about anything, and the three of them stared at me, stunned. I said I was sorry, drained and refilled my glass, noting that Teresa seemed genuinely hurt; I found that to be a greater indication of her affection for me than the fact that she had favorites among my poems. We’ll read it, I said.

Lerner is the son of a feminist psychologist who wrote a noted book in the field in the mid 80s. I see it in second-hand bookstores all the time – it’s called The Dance of Anger.

***