review coming soon

Category: 2020s

Comedy Book (Jesse David Fox, 2023)

Comedy book is a rare project, an updated nonfiction book about stand up comedy and its position in culture today. Most books on the topic are shticky novelty efforts, but this one takes its topic seriously – without being boring. In the vein of comedy nestor Kliph Nesteroff, culture critic Jesse David Fox has written a fine book on American comedy and how it relates to media, free speech, cancellations and our changing expectations on what should make us laugh.

It’s rare for me to read a book so filled with current events and topics that have been in the news. Mentions of many things from last five-ten years: covid, maga, woke, alt-right, BLM. A lot of the book takes up issues about identity politics, and analyses them through the lens of the comedy world. The book is structured around eleven chapters named for keywords: comedy, audience, funny, timing, politics, truth, laughter, the line, context, community, connection.

The age-old question: what is comedy? is adressed throughout, with theories and arguments about how our ideas about comedy have gone through many changes, and they continue to change, increasingly rapidly. One thread in the book picks up on the idea of post-comedy, where comedians do shows more or less without jokes. A typical example of that is a show called Nanette by Hannah Gadsby, which talks about abuse, or Tig Notaro’s show about her cancer. The comedy world is divided about it, one camp saying ”funny is funny” and the other holding on to ”it depends on the context” (which, post-Oct 7, is a complicated phrase). Fox is in the latter camp, and characterizes funny is funny-crowd as naive and closed off. I guess it takes a comedy critic to write a book like this, because no-one else would take comedy as seriously. Few people would make the effort to analyze comedy this rigorously, cause it’s hard to do without having the frog die (as the old E.B. White quote goes).

Reading this book makes me realize my generation is probably in a unique position with regards to comedy. Having been exposed to sitcoms since childhood, then seen the rise of internet humor and the establishment of a new comedy scene, largely spread through podcasts, we are familiar with a variety of comedy modalities, which someone who is a teenager today might not be.

One of the most interesting transitions in the comedy-sphere since the early 2000s is the rise of Jon Stewart and his role in the comedization of politics (or should it be the politicization of comedy? Probably both). Fox dedicated a chapter to this (and also has an extended riff on ”too soon”-jokes about 9/11). And now I hear that Jon Stewart is coming back to television, after his retirement six years ago.

Comedy is the the new ultimate frontier of what is allowed to say in our culture, as Stephen Metcalfe presciently observed in an article a decade ago). Granted, from George Carlin’s seven words to Joe Rogan’s incendiary podcast, comedians have always liked to push the boundaries, but with our increasingly polarized culture, there are plenty of new boundaries to push and a whole lot of new niche audiences there to listen.

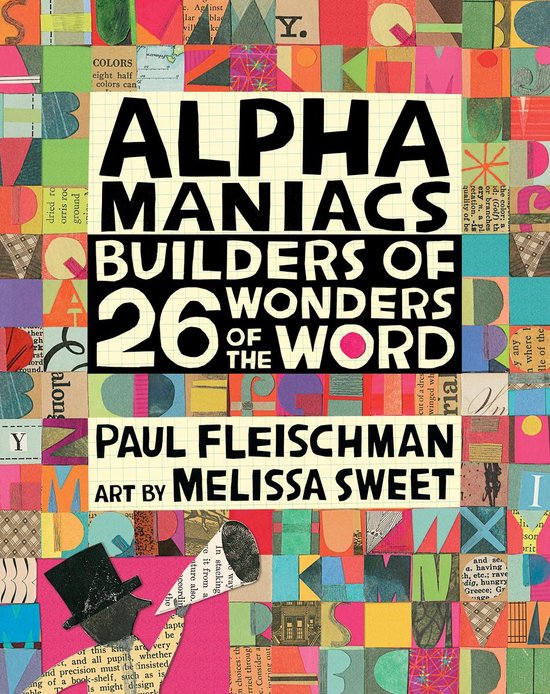

Alphamaniacs (Paul Fleischman, 2020)

Alphamaniacs is a fun book for all linguistically inclined readers! It is structured around 26 short bios of language innovators (why 26? One for every letter of the English alphabet). The selection spans from blink-writer Jean-Dominique Bauby to Ludvik Zamenhof, the founder of Esperanto. There is an emphasis on the playful, which is reflected in the tone of the writing, and also the choice of profiles. A bunch of the profiles are of artists who made typographical artworks, others are of hyperpolyglots, yet others who revel in art of inventing languages. But it is grounded in the alphabet. One chapter covers an American who transfers the Hebrew tradition of assigning numbers to letters, what s called Gematria, to English. Several of the areas have since long been niche interests of mine, but I’ve never seen them collected in a slim volume like this. Classics like universal languages, nonsense typography, experimental literature like Perec and Queneau. Other highlights include crossword wizards and the curious inventor of “PL8SPK”. I knew a lot of the material already, but it was still a joy to breeze through the book. Recommended for all language enthusiasts!

Racée (Rachel Khan, 2021)

Racé is the word Khan invents to counteract racisé and racialisé. The English word for the latter is racialized, which came into common parlance in America about 15-20 years ago. But Khan is not American, she’s French, and she has her own ideas on how to tackle questions of race. She want to push back on the idea that we as humans should compartmentalize in identity groups based on artificial categories like black and white. She is not black or white, she is a lot of things, she means to say, and doesn’t want to be reduced to a one-dimensional category.

She shares this idea with American thinkers like Thomas Chatterton Williams and Coleman Hughes. They are of so-called mixed origin and maybe this fact gives them a particular viewpoint on these kinds of matters. Khan questions the value of seeing identity in terms of mixité, and asks rhetorically, what is a mixed marriage and what is a mixed person?

The word racialisé, Khan informs us, is from Feminist sociologist Colette Guillamin, elaborated on in a book from 1973. But in America the use of this word seems to have been pioneered by theorists Omi & Winant during the 80s.

Throughout the book she returns to quotations of fellow French writer Romain Gary, and to a lesser extent Edouard Glissant. A Romain Gary quote: On est tous des additionés, we’re all “additioned”, a sentiment Khan must sympathize with.

Rachel Khan criticizes the notion of safe spaces, rooms or meetings exclusively for people of a certain origin. The very idea makes her uncomfortable, and she offers that her safe space is a room of different people, ”Mon safe space est un space des melanges”. The text is incidentally rife with wordplay: “les maux d’un climat déréglé et les mots d’un climat délétère”, or ”c’est un trou noir, c’est troublant”.

This book is full of ideas that leaves the reader with questions and after reading only a handful of them seem settled. The fact that its ideas live on unresolved in the reader makes it hard to write a definite review. I’m undecided on what I think about some of these issues and I still ponder the notion of mixedness, and how Khan’s mixed origins must have influenced her thinking.

She discusses words she dislikes (quota, afro-descendant, racisé, souchien), words she likes (intimacy, silence, creolization) and words she finds non-helpful (mixité, diversity, ”vivre ensemble”). Her book speaks to the experience of being mixed but its goal is to counteract the idea of race categories and therefore also of the notion of “mixed race”. Or maybe the goal is to offer an alternative narrative? She constantly feels to be inbetween:

J’étais juive chez les Noires, noire chez les Juifs, juriste chez les artistes, artiste chez les politiques… Maintenant, je suis à chaque fois quelque chose « de service » : « la comédienne de service » chez les intellectuels ou « l’intello de service » chez les sportifs.

I was Jewish among the blacks, Black among the jews, lawyer among the artists, artist among the politicians… Now, I’m at every instant something “of service”: comedian of service among the intellectuals or intellectual of service among the athletes.

This sense of being caught between worlds is increasingly common as the world continues to move around. The notion of race, whiteness, blackness, otherness is in transition. I’m happy that there are other voices than those who one-sidedly advocate a separatistic identity show. But sometimes, in her eagerness to think universalistically, Khan forgets that some things really are particular. And maybe just as some people have a hard time understanding her perspective as someone from mixed origins (and yes, in a sense, everyone is mixed) she might have a hard time understanding those who are nor perceived as mixed.

She writes that she could only have come into being in France, where the values of equality and democracy led her parents into communion from entirely different worlds. A world where an eastern European Jew whose parents survived the Holocaust could build a family with an Animist Muslim Senegambian man. She means that she has the values of France inscribed in her veins because in her view they were the basis for their coupling in the first place. This book contains a lot of high-minded thinking, and I’m sure some of it is very noble. I’m just not sure the world is ready for it. Maybe she is a pioneer and it might just be that her thinking will become widespread in the coming years.

La voix du terroriste (Claude Kayat, 2023)

This book by fascinating writer Claude Kayat can be seen as a meditation on the current state of identity and the shifting kinship and enmity between different faith groups. The setup is shockingly direct; during a deadly terrorist attack and hostage situation in a Paris synagogue, the terrorists inexplicably let one of their key hostages go, without any explanation. The newly released captive, Ludovic Lévy, is deeply relieved, but dumbfounded as to why he was set free. And didn’t he recognize something familiar in the voice of one of the captors?

After some investigation, he believes that the terrorists were his childhood friends Abdallah and Mourad, since estranged. Lévy wants to understand why they became terrorists, and the terrorists, naturally, want to avoid identification. A sort of detective story ensues, where they negotiate their respective positions with reference to faith, history, family and power. We get to follow both parties in interspersed chapters, adding to the suspense of the narrative. An interesting subplot is that one of the terrorists is a “grand blond” who has a Swedish mother and a Tunisian father, whose aberrant appearance is part of how they can be identified.

It is a story of how we are all human, and that we should be able to live together. Themes from Kayat’s earlier novel la Paria can be discerned, which also deals with the sometimes taut relations between Jews and Arabs – but this time in Paris instead of the Galilee. As with la Paria, the intertwined stories and fates of the characters must be reminiscent of pre-colonial Tunisia were Jews and Muslims lived closer to one another. One can sense that Kayat hearkens back to those days and wants to recall that it is possible to achieve again. Only a writer like Kayat, who is familiar with both of these milieux would be able to write a story like this, and he does it with aplomb. Sometimes it veers into implausible territory (the final journey of Mourad to Stockholm), but then one has to be reminded that it is meant as a parable. La voix du terroriste is a short novel, but it packs a big punch throughout 143 pages, and its message is loud and clear. The absence of a final resolve is surely meant to mirror real life, as if to remind the reader that it is up to us (you and me and everyone else) to change things.

Review of La Voix du terroriste in English by Christophe Prémat

review in French by Albert Bensoussan

My review of Claude Kayat’s La Paria (2019)

House of Glass (Hadley Freeman, 2020)

Longtime journalist at the Guardian Hadley Freeman (since then moved to the Sunday Times) has covered topics of pop culture, politics and feminism. She had the idea to write this book for 20 years, but never knew how to start. She first wanted to write about her grandmother, but then expanded it to include all the siblings, as their stories told a story of the 20th century.

The story revolved around Freeman’s grandmother Sala, and Sala’s three brothers, from Poland to France, and in the case of Sala, on to the US. Freeman herself was born in America and grew up there, until her family moved to the UK when she was 11. It’s a cosmopolitan story, but the transfuge is motivated by oppression. The Glass family are Jews, and a series of pogroms in Chrzanow leads them to decide to emigrate to France in the early 1900s. Thinking they were safe from harm in France, it came as a shock that France became occupied and set up a collaborationist government which persecuted Jews.

It’s a hefty history lesson, with details about the Pétainist leadership. It is also a personal story, about a young girl’s relationship to her grandmother. It’s impressive how well Freeman has been able to weave the story, with an unusual amount of detailed research. Maybe some of it was the result of artistic license? The four Glass siblings all have interesting stories, but the standout is Sander, who reinvents himself as the fashion mogul Alex Maguy in France.

Freeman puts in commentary on political issues throughout the text, in true journalistic fashion, which I believe benefits the text and makes it feel fresh. She also includes her thoughts on Jewish identity and integration. I recently read Anne Berest‘s “La Carte postale” which has a lot of points in common with Freeman’s book. Both are books about discovering a French Jewish family history, by focusing on four different individuals. The writers are also of the same age (Freeman born in 1978, Berest in 1979). Both had relatives who were friends with world class painters like Picasso and Picabia. Both had relatives detained in the French internment camp Pithiviers. They both have also written books about fashion (The Meaning of Sunglasses: A Guide to (Almost) All Things Fashionable; How to be Parisian wherever you are). The difference is in how they chose to write, because Berest wrote in a novelistic style, whereas Freeman chose a journalistic approach.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect (Andrés Stoopendaal, 2021/2023)

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is a name given for the tendency for low-performing people to overestimate their performance, and for high-performing people to underestimate their performance. In other words: dumb people see themselves as smarter than they are, and smart people see themselves as dumber than they are. Why this phenomenon has been chosen as the title for this Swedish novel (in English translation this fall by Simon & Schuster) commenting on contemporary culture is not totally clear.

It all starts with a dinner party (or parmiddag in Swedish) where the protagonist mentions Jordan Peterson, a psychologist who has been vocal about the policing of language around trans issues. But because Peterson’s name isn’t followed by a clear condemnatory diatribe, the other guests become uncomfortable. “You can’t possibly mean he has something noteworthy to say” is the response, and just in time for dessert the evening becomes increasingly uneasy. It is this tension that the book is based on.

One could assume it is a joke on the reader, to sprinkle the text full of culture war-laden buzzwords and terms gleaned from Wikipedia articles describing psychological research. But I don’t think it is. I think the writer has immersed himself in this world and let it tumble around in his writerly mind for a while, and the end result is this book, which I don’t think is premeditated or really planned. It is a pretty funny book. I wonder though, to what degree the humour is culture-bound to the Swedosphere (suèdosphère?). I should be in prime position to judge, as I am pretty well-versed in both Swedish and English.

Some parts of the book must be hard to translate, like the Sweden-specific dread around a certain political party, and lots of comments on social customs or Swedish middle class culture. I almost felt embarrassed at times. Stoopendaal dissects the Swedish cultural obsession with consensus and general avoidance of social tension. Several sections of the book deals with current events and cultural upheavals like the metoo movement, and its repercussions on the Swedish literary establishment.

In Swedish there is a word for English terms taken in directly as loanwords without consideration – anglicism. This book is FILLED with them, both intentional and unintentional. A lot of English words and expressions are employed, as if they have slipped through to the Swedish usage. Sometimes they ring very false. This might be an intentional effect, but I don’t know. It has to be nearly impossible to convey this linguistic interplay in the English translation though.

Sometimes i get the sense that Stoopendaal wanted to review a book or just express a fleeting thought, because there are a lot of digressions of that kind. This is common practice in contemporary novels, an autofictive influence. Stoopendaal drones on about Pomeranian dogs (which inspired the choice of cover design), the culture of the ultra rich through a book by Sigrid Rausing, and some notes on writing with Stephen King and Swedish stalwart Jan Guillou.

He also dedicates a chapter to French writer Michel Houellebecq, which invents a story where Houellebecq is visited by an agent of the French Secret Police. This chapter has captured the attention of Houellebecq enthusiasts internationally, and might be a contributing factor to why he book has been picked up for translation. Stoopendaal also seems to have found inspiration in the writing of C.G. Jung, alt-right expressions and computer game lingo. It is refreshing to read satiric treatments on current cultural trends like podcasts, words like “safe space”, New Public Management, and various current thoughts on masculinity, sexuality, class, politics and “just-in-time production”(!).

Another astute observation is the now ubiquitous phenomenon of couples sitting at home each with their own tablet och phone watching separate screens, but sitting next to one another in a sofa. Here is the excerpt (translated by the reviewer):

Something about this situation, this setting, with me in the easy chair with my laptop computer, Maria with her iPad, resting on the sofa, felt very, even brutally familiar. Which it was. It was most certainly a painfully ordinary situation in the everyday lives of millions of people, regardless of where on the globe they lived. Two or more people in a living room, each of which are busy or rather wholly absorbed by their electronic plaything, together and close to one another physically, but at the same time very much solitary. Did Maria need my physical presence in this room? Did I need hers? No, in a fundamental sense neither of us needed the other, not in this situation, not until one of us started to demand something of the other. I could at any moment request Maria’s attention. But why? For her to give me some sort of validation? I didn’t feel any need for such validation, in any case not in this particular situation.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect by Andrés Stoopendaal

All in all, a pretty funny book, with things to say about our current moment which amounts to a good time, with plenty of moments of mirthful recognition. I’m not sure it is meant as a comedy, though. My take is that the book doesn’t have a set purpose, it’s more of an expression of one person living in the early 2020s.

Emotional Inheritance (Galit Atlas, 2022)

Reading tales from therapy is a double-edged sword. The stories are so heavy, but at the same time they are strangely nourishing. There is something rewarding in taking in heavy stories. And this book does contain some devastating stories! There is a focus on sexuality, which I’m not really used to. I guess the Esther Perel-ness of it all feels very female. Several stories included instances of trying to heal hurt with sexuality. Female sexuality is probably more “weaponized” in the lifeworld of women, the vantage points are not equal when compared to men. Radical equality is probably not even possible because of the differences in sexual setup! Female perspectives are needed for men – and also vice versa.

Anyway, I’ve read a handful of books of ”tales from psychotherapy”, the first one being my grandmother’s dog-eared copy of Love’s Executioner by Irvin Yalom. I was fascinated by the vignettes of personal problems, the therapist’s view and then the unfolding of the process. I revisited the genre when I started undergoing therapist training myself, reading more. Stephen Grosz’s Examined Life was a compelling one. A family friend in New York sent me Robert Lindner’s Fifty Minute Hour, for a vintage taste (it was written in the 50’s). This time around I found Galit Atlas’ Emotional Inheritance, which focuses on intergenerational transmission of psychological trauma. There are eleven case stories divided into three parts, grandparents, parents and ourselves. I’m very interested in the generational view, which to me seems underdeveloped in psychotherapy. This book provided several good examples of this perspective, all drawn from Atlas’ own practice.

Throughout the book, Atlas is candid about her own thoughts and insecurities during the sessions, and she also opens up about her own complexes and traumas. In an interview she mentions that she considers her research to also be ”me-work”, meaning that her interest in trauma originates in her own traumatic experiences, which she processes as she helps others as well. This is the notion of the ”wounded healer”, common in folklore. She mentions the all-pervasive trauma machine that is the Israeli military (as Atlas is Israeli, she served in her youth). She also talks about the trauma of her parents’ families being forced to leave Iran and Syria during the period of persecution called Farhud. Another is her own experiences of relationships.

One of the stories in the book is the unbelievable account of a man who, although having grown up as an only child, senses that he had a twin brother who died and then discovers it to be true. What’s more, this phenomenon isn’t even that uncommon. Another memorable story is about a young woman whose family had been ripped apart when her grandmother accused the young girl’s (innocent) older stepbrother of abuse because of a sexual abuse trauma the grandmother experienced in her own youth. Such is the human comedy, tragic and flawed. I thought there would be more about the Shoah, but in a way it was better to keep it more universal. One fascinating point Atlas returns to is the fact that a lot of the patients activate a complex when they turn the same age as their parents, or when their children become the same age as they were when the had a defining experience. I wasn’t aware of how common this seems to be.

Eurotrash (Christian Kracht, 2021)

Swiss enfant terrible Christian Kracht writes a short book about taking a trip with his aging alcoholic mother. The narrative is sprinkled with mostly ironic (and sometimes funny) comments on contemporary culture, and lots and lots of references to expensive goods, literature, David Bowie and also Kracht’s own literary career. I wouldn’t hesitate to call this an instance of autofiction, which is what seems to be the most viable and reward-for-effort-intensive form of literature nowadays. Readers want to read a story, and also want some gossip about the writer. Writers don’t have to try as hard writing this kind of autobiographical life writing compared to traditional novels, and they get the added bonus of getting some spin to their “personal brand”.

Kracht does craft funny sentences, and has a knack for the absurd humor. It is sometimes too based in a rich, Switzerland-based world for my tastes, however. He also has a tendency to include gross and disgusting details in his stories. I learned this from reading his Imperium (2012) which included a protagonist who ate his own scabs (highly unpleasant). That might be just part of his whole épater-le-boozwazee shtick.

I suspect that the story is really about himself trying to make peace with his family history. He sometimes writes his mother’s lines in his own voice, which is probably meant as a clue.

The Nineties: A Book (Chuck Klosterman, 2022)

I was born in the late 80s. My childhood was in the 90s. I became a teen in the new millenium. 90s culture informed my every move growing up. It was there all through the horrid ”aughts” too. My view is that there was no placeholder culture to take over the banner from the 90s when the new decade came , so the 00s were mostly rehashed 90s culture and revival waves in an infinite bad loop (i’m looking at you, skinny jeans rock revival). The 90s ethos reigned supreme for 20-25 years or more! It started fizzing out with the notion of the ”hipster” (of which it was an offshoot) and died with the advent of so called gen z zoomer culture of respectability and 1950s ethics.

All this to say that I feel very much part of the target audience for this volume of essays about the years 1990-1999 (of course Klosterman latches on to the current practice of loose end definitions, roping it in to ’89 to ’01 (Berlin Wall, Twin Towers)).

Its twelve essays range a bunch of topics, some of which interest me (the changing face of music culture, the rise of the nascent internet, celebrity ethics, vhs cinema) and some I would never have read unless they were part of this book (college basketball, Dan Quayle, trends in soft drinks). Klosterman was born in 1965, so he was well into adulthood when the 90’s began, so his perspective differs from mine. He adapted to 90s culture as an adult, whereas I swam in its wake.

Anyway, the essays meander and move from one thing to the next, filled with the kind of tidbits and ephemera only available to those who do strenuous research. The biggest topic for me in assessing the 90s and how they differ from our current climate is the complete change in what is considered cool, or to speak in bourdieusian terms, consecrated. The epitome of 90s affectation was to not care, to use irony, and to make obscure references. Not so today. There is something of a ”new sincerity” among younger people today, and their worldview is so massively built around silicon valley communication ecology that the generational rift is probably greater than ever before.

Having devoted much of my own youth to movies, I found the chapter on cinema of particular interest. Movie culture was probably in its apex in the 90s. Films were considered important in a way they don’t anymore. Also important was the rise of VHS and video rentals. Klosterman explains the rise of a new kind of filmmaker who had seen all the movies growing up, which created a hyperaware style of movies, epitomised by Quentin Tarantino. Movies were water cooler talk in the 90’s; it was a sort of monoculture that created a sense of coherence.

What is arguably most interesting when comparing the 90’s and today is, in my view, the effect of the internet on human affairs. To this Klosterman devotes parts of chapter 6. He writes about early mp3 filesharing with Napster, which to my recollection more belongs to the early 00’s (he gets a pass on the technicality that Napster launched in late ’99).

There is also a lot of material about the dynamics of cultural memory, about what is remembered and what is forgotten, and why. A recurring phrase is ”times change as they always do”. That’s a pretty shallow statement when you think about it. But these kinds of musings on the passing of time are sprinkled throughout, and I think Klosterman even wrote a whole book on that theme in 2016, called What if We’re Wrong? (but I haven’t read it).

A trademark klosterman gimmick is to take two seemingly unrelated people and juxtapose them as similar or opposites to prove a point. He contrasts Alan Greenspan with Oprah Winfrey. Kurt Cobain and Tupac Shakur. Even Tiger Woods and rap singer Eminem. New stuff comes to light in these exercises.

I can’t pick up all the threads this book led my thoughts on to, but to me it was a pretty good ride. It seems deliberately kaleidoscopic, maybe because Klosterman wants to fit so much stuff in. It never feels cramped, though. A criticism of the book has been that it is too US-centric, and that it doesn’t mention the Balkans war. I don’t know if Klosterman is the right fit for writing on the Balkans war. I think he’d do better writing something about ”culture jamming”, adbusters or cyberpunk; three very 90’s phenomena that are absent from the pages of this book.

In the last chapter he proposes a theory that the 90’s were the last decade of identifiable cultural look, because the 00’s and 2010’s have both been so muddled and hard to define. This is an interesting statement, that echoes Kurt Andersen’s much-discussed 2012 Vanity Fair article “You Say You Want a Devolution”, where he contrasts 1992 to 2012, and drives an argument about cultural stagnation. A similar thesis is proposed in music critic Simon Reynolds‘ 2011 book Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past. These ideas have fallen out of favor, possibly because style and pop culture is less regimented than under 20th century conditions: ten years on, and we still have a hard time formulating a definitive typical 2010s mainstream style. My bet is that the arenas for expression have migrated more online than in music and clothes, which to older people is hard to understand.

Nineties is part of a current 90s revival, grappling with the cultural legacy of the period. Other recent books about the 90’s include Teddy Wayne’s 2020 book Apartment, and the Ben Lerner book The Topeka School. The movie Landline from a few years ago and the recent miniseries Lea’s Seven Lives are also part of this trend. It must be that one cohort of writers have now reached the age where they look back at their younger years, and want to depict it. I’m glad they did, because I’m here to read it.