review to come

The Body Keeps the Score (Bessel van der Kolk, 2014)

Bessel van de Kolk once received a request to help me find an internship. Or at least, that’s what I was told. No internship came of it, in the end. This was around 2014, and I guess one reason for not responding was that he was busy finishing this book – which bears the title of his pathbreaking article on his trauma research from 1996. What happened to the term trauma between those years to bring it in to such prime focus? Initially, van der Kolk pursued the field because of his own sense of traumatization during the WW2, as a boy in occupied Amsterdam. Later, as a young MD in the US, he began observing Vietnam veterans and their inability to recover from wartime experiences. van der Kolk outlines his own interest in the field in the beginning of the book, and his own story mirrors the evolution of the term from world wars to its current status as a word that has enjoyed exponentially increased dissemination the last ten years.

The book refers to a lot of studies of trauma, PTSD and dedicated a lot of pages to describing different modalities of treatment. He tells of CBT, EMDR, “bodywork” but also of drumming, theatre and song.

I recently partook in a four day course on a trauma treatment method called PE, where I asked the instructor what she thought about Bessel van der Kolk’s work. She scoffed at the mention of his book, which surprised me. My understanding was that he might be controversial, but still a respected authority on trauma. This proved to no longer be the case, at least for this particular instructor.

Later I found out that van der Kolk has been attacked by various journalists and writers for making the word trauma popular, and thereby twisting its meaning. It has become chic to refer to something awful that happened in the past as a trauma, and what once was only associated with the terrors of war, torture and assault now encompassed lighter problems like squabbles, neglect and other such slights. The death of a pet goes from being a sad event to being seen as an insurmountable emotional hurdle. This change has also fueled a movement that sees a system of generational trauma connected to historical racial injustice.

I am particularly invested in the idea of generational trauma since I am two generations down from holocaust victims, which is a fact that informs my self-identity (rightly or wrongly). My father’s life and upbringing was seriously stumped because of his parents had spent time in what is called concentration camps, a term I have a hard time with. His life informed my life. And my life informs my children’s lives.

My grandmother knew Bessel and used to attend his conferences. She even took to habitually carrying the little black and red bag from the conference as her usual carry-all. In big red letters on black background it said “TRAUMA STUDIES CONFERENCE”, which I guess gave her some kind of thrill to parade around with. She was herself a victim of trauma – and a wounded healer later helping other survivors.

Back to Bessel – he has recently also been accused of acting uncavalier at his workplace, which lead to his termination. This in addition to the claim that he has blurred the notion of trauma currently puts him in a somewhat disgraced position. One might say that van der Kolk has misshaped modern perceptions of trauma, but I believe that this tendency was evident in the zeitgeist regardless of his particular efforts. We are now in a moment where a countervailing force is emerging. This is represented by people who rather emphasise words like grit, resilience, robustness, and antifragility, to use a coinage by Nicholas Nassim Taleb. Another writer, Abigail Shrier, argues that “therapy culture” has made a whole generation into wimpy snowflakes, in her new book Bad Therapy. As usual, I think the truth lies somewhere in between these extremes. I took offense at reading Shrier’s ranty prose dismissing a lot of research findings. Sadly this is not unusual when a non-expert reviews psychological concepts. She pisses on epigenetics, on generationally inherited trauma research (conducted by Rachel Yehuda et al) on Bessel’s whole life’s work.

I am beginning to think there are two types of trauma researchers; those who’ve experienced trauma themselves and want to understand it, and those who want to make a career and happened to choose trauma as a specialty – and therefore don’t possess enough of an understanding of the phenomenon to really grasp what it is. I’m not arguing that one needs to suffer from the particular ailment one treats or does research on as a professional – that would be absurd – but I think in this particular case it might help.

Maybe You Should Talk to Someone (Lori Gottlieb, 2019)

A therapist memoir where we get to follow the therapist as practitioner, but also as a client in therapy herself – which is an unusual setup for this kind of book. The subtitle is “a therapist, her therapist and our lives revealed”. It seems to me that the book does a pretty good job of conveying the ins and outs of being a therapist. We also get a lot of backstory on Gottlieb’s career before becoming a therapist, which she seems to want to integrate in the story. She started in TV production, working on shows like E.R, then went to medical school, dropped out, started working in journalism. It was when she had some regrets about having dropped out of med school that someone suggested she might consider becoming a therapist. I know this because she tells the story in the book. She also tells the story of a few of her patients, and unlike other books of this kind, she includes precious vignettes that bring up various embarrassing or awkward moments that come with the job of a therapist. What happens when you bump into a client unexpectedly at the store? And what are the downsides of using Google to learn about your therapist’s private life? Interwoven is also the story of how she got pregnant, and the devastating breakup that leads her to seek out her own therapist. She tells us about her weekly collegial meetings where they discuss difficult current cases, and use insider slang about video sessions.

It is all very well crafted and it shows that Gottlieb is a writer, because even though some scenes come across as a bit unbelievable, she does a good job putting it all together; story, suspense, a bit of educative content about therapy all tied together with a human interest angle. Sometimes it’s a bit heavy on the fluff, but, hey, I guess that’s because it’s aiming for a large audience. It is very readable, and the chapters are just right in length for it to feel like you should read just one more.

All in all, a triumph of a book, which probably does a lot for spreading the gospel on the benefits of therapy. As a therapist, I found it pretty funny.

Comedy Book (Jesse David Fox, 2023)

Comedy book is a rare project, an updated nonfiction book about stand up comedy and its position in culture today. Most books on the topic are shticky novelty efforts, but this one takes its topic seriously – without being boring. In the vein of comedy nestor Kliph Nesteroff, culture critic Jesse David Fox has written a fine book on American comedy and how it relates to media, free speech, cancellations and our changing expectations on what should make us laugh.

It’s rare for me to read a book so filled with current events and topics that have been in the news. Mentions of many things from last five-ten years: covid, maga, woke, alt-right, BLM. A lot of the book takes up issues about identity politics, and analyses them through the lens of the comedy world. The book is structured around eleven chapters named for keywords: comedy, audience, funny, timing, politics, truth, laughter, the line, context, community, connection.

The age-old question: what is comedy? is adressed throughout, with theories and arguments about how our ideas about comedy have gone through many changes, and they continue to change, increasingly rapidly. One thread in the book picks up on the idea of post-comedy, where comedians do shows more or less without jokes. A typical example of that is a show called Nanette by Hannah Gadsby, which talks about abuse, or Tig Notaro’s show about her cancer. The comedy world is divided about it, one camp saying ”funny is funny” and the other holding on to ”it depends on the context” (which, post-Oct 7, is a complicated phrase). Fox is in the latter camp, and characterizes funny is funny-crowd as naive and closed off. I guess it takes a comedy critic to write a book like this, because no-one else would take comedy as seriously. Few people would make the effort to analyze comedy this rigorously, cause it’s hard to do without having the frog die (as the old E.B. White quote goes).

Reading this book makes me realize my generation is probably in a unique position with regards to comedy. Having been exposed to sitcoms since childhood, then seen the rise of internet humor and the establishment of a new comedy scene, largely spread through podcasts, we are familiar with a variety of comedy modalities, which someone who is a teenager today might not be.

One of the most interesting transitions in the comedy-sphere since the early 2000s is the rise of Jon Stewart and his role in the comedization of politics (or should it be the politicization of comedy? Probably both). Fox dedicated a chapter to this (and also has an extended riff on ”too soon”-jokes about 9/11). And now I hear that Jon Stewart is coming back to television, after his retirement six years ago.

Comedy is the the new ultimate frontier of what is allowed to say in our culture, as Stephen Metcalfe presciently observed in an article a decade ago). Granted, from George Carlin’s seven words to Joe Rogan’s incendiary podcast, comedians have always liked to push the boundaries, but with our increasingly polarized culture, there are plenty of new boundaries to push and a whole lot of new niche audiences there to listen.

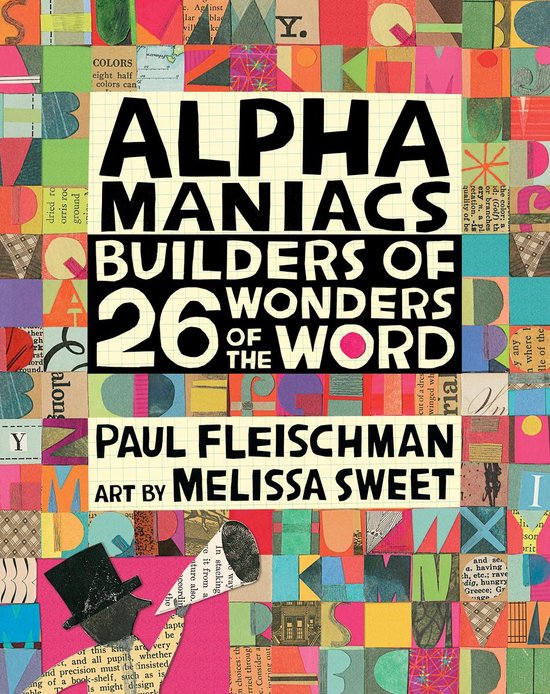

Alphamaniacs (Paul Fleischman, 2020)

Alphamaniacs is a fun book for all linguistically inclined readers! It is structured around 26 short bios of language innovators (why 26? One for every letter of the English alphabet). The selection spans from blink-writer Jean-Dominique Bauby to Ludvik Zamenhof, the founder of Esperanto. There is an emphasis on the playful, which is reflected in the tone of the writing, and also the choice of profiles. A bunch of the profiles are of artists who made typographical artworks, others are of hyperpolyglots, yet others who revel in art of inventing languages. But it is grounded in the alphabet. One chapter covers an American who transfers the Hebrew tradition of assigning numbers to letters, what s called Gematria, to English. Several of the areas have since long been niche interests of mine, but I’ve never seen them collected in a slim volume like this. Classics like universal languages, nonsense typography, experimental literature like Perec and Queneau. Other highlights include crossword wizards and the curious inventor of “PL8SPK”. I knew a lot of the material already, but it was still a joy to breeze through the book. Recommended for all language enthusiasts!

Les bagages de sable (Anna Langfus, 1962)

Anna Langfus is a forgotten writer; to the extent that she’s remembered at all, it’s as the recipient of the Goncourt prize of 1962, for Les Bagages de sable. She was a refugee from the second world war, who grew up in a Jewish family in Lublin, Poland. She survived by adopting the identity of a non-Jewish friend, Maria. After war’s end, she felt unsafe during the anti-Jewish public sentiment in Poland and made up her mind to leave for France. There she started writing plays and managed to publish three books, somewhat based on her own experiences, 1960, 1962 and 1965. Bagages de sable is the second one of these books. The title means luggage of sand, which strikes me as a good image. When it was translated to English in 1965, it got the title “The Lost Shore”.

It is about a young woman displaced from another country, to France. She meets an older man with whom she enters an affair. It is never mentioned what country she is from, or what she has lived through, but there is a palpable sense of a wound or a trauma in her past. In this way, I believe it is quite an innovative book, where she touches upon themes later explored by the likes of Georges Perec, and China Miéville in This Census-taker.

I have a pet theory where female holocaust survivors who wrote about their experiences often wrote three books, and that this was a kind of exorcising of their trauma. The first book about their childhood, the second of their time in the camps and the third about their life afterwards. I don’t think Langfus really fits that mould, but she was one of the earliest survivors to write about their experiences. Along with Piotr Rawicz (also originally from Poland) and Elie Wiesel (who wrote in Yiddish) she was among the first survivors to deal with their survivorship in literary form in France, and among the first of any country, really.

She is not entirely forgotten, however. The fact that she was awarded the Goncourt Prize (France’s highest literary honor) helps to slow her descent into obscurity. There are also memorial plaques in France and in Poland, as well as a community library bearing her name, in Sarcelles, Paris. Recent years has also seen a Facebook group created to commemorate her work. If she hadn’t died suddenly in 1966 maybe she had been able to write more books. She was in the process of writing a book while she died, according to her biographer Jean-Yves Potel, who wrote “Les disparations d’Anna Langfus” in 2014, a book which sparked renewed interest in Langfus and her writing.

_______

This is the second time I write about a holocaust survivor in the Year club. I previously wrote about Herman Sachnowitz in 2021.

Racée (Rachel Khan, 2021)

Racé is the word Khan invents to counteract racisé and racialisé. The English word for the latter is racialized, which came into common parlance in America about 15-20 years ago. But Khan is not American, she’s French, and she has her own ideas on how to tackle questions of race. She want to push back on the idea that we as humans should compartmentalize in identity groups based on artificial categories like black and white. She is not black or white, she is a lot of things, she means to say, and doesn’t want to be reduced to a one-dimensional category.

She shares this idea with American thinkers like Thomas Chatterton Williams and Coleman Hughes. They are of so-called mixed origin and maybe this fact gives them a particular viewpoint on these kinds of matters. Khan questions the value of seeing identity in terms of mixité, and asks rhetorically, what is a mixed marriage and what is a mixed person?

The word racialisé, Khan informs us, is from Feminist sociologist Colette Guillamin, elaborated on in a book from 1973. But in America the use of this word seems to have been pioneered by theorists Omi & Winant during the 80s.

Throughout the book she returns to quotations of fellow French writer Romain Gary, and to a lesser extent Edouard Glissant. A Romain Gary quote: On est tous des additionés, we’re all “additioned”, a sentiment Khan must sympathize with.

Rachel Khan criticizes the notion of safe spaces, rooms or meetings exclusively for people of a certain origin. The very idea makes her uncomfortable, and she offers that her safe space is a room of different people, ”Mon safe space est un space des melanges”. The text is incidentally rife with wordplay: “les maux d’un climat déréglé et les mots d’un climat délétère”, or ”c’est un trou noir, c’est troublant”.

This book is full of ideas that leaves the reader with questions and after reading only a handful of them seem settled. The fact that its ideas live on unresolved in the reader makes it hard to write a definite review. I’m undecided on what I think about some of these issues and I still ponder the notion of mixedness, and how Khan’s mixed origins must have influenced her thinking.

She discusses words she dislikes (quota, afro-descendant, racisé, souchien), words she likes (intimacy, silence, creolization) and words she finds non-helpful (mixité, diversity, ”vivre ensemble”). Her book speaks to the experience of being mixed but its goal is to counteract the idea of race categories and therefore also of the notion of “mixed race”. Or maybe the goal is to offer an alternative narrative? She constantly feels to be inbetween:

J’étais juive chez les Noires, noire chez les Juifs, juriste chez les artistes, artiste chez les politiques… Maintenant, je suis à chaque fois quelque chose « de service » : « la comédienne de service » chez les intellectuels ou « l’intello de service » chez les sportifs.

I was Jewish among the blacks, Black among the jews, lawyer among the artists, artist among the politicians… Now, I’m at every instant something “of service”: comedian of service among the intellectuals or intellectual of service among the athletes.

This sense of being caught between worlds is increasingly common as the world continues to move around. The notion of race, whiteness, blackness, otherness is in transition. I’m happy that there are other voices than those who one-sidedly advocate a separatistic identity show. But sometimes, in her eagerness to think universalistically, Khan forgets that some things really are particular. And maybe just as some people have a hard time understanding her perspective as someone from mixed origins (and yes, in a sense, everyone is mixed) she might have a hard time understanding those who are nor perceived as mixed.

She writes that she could only have come into being in France, where the values of equality and democracy led her parents into communion from entirely different worlds. A world where an eastern European Jew whose parents survived the Holocaust could build a family with an Animist Muslim Senegambian man. She means that she has the values of France inscribed in her veins because in her view they were the basis for their coupling in the first place. This book contains a lot of high-minded thinking, and I’m sure some of it is very noble. I’m just not sure the world is ready for it. Maybe she is a pioneer and it might just be that her thinking will become widespread in the coming years.

La voix du terroriste (Claude Kayat, 2023)

This book by fascinating writer Claude Kayat can be seen as a meditation on the current state of identity and the shifting kinship and enmity between different faith groups. The setup is shockingly direct; during a deadly terrorist attack and hostage situation in a Paris synagogue, the terrorists inexplicably let one of their key hostages go, without any explanation. The newly released captive, Ludovic Lévy, is deeply relieved, but dumbfounded as to why he was set free. And didn’t he recognize something familiar in the voice of one of the captors?

After some investigation, he believes that the terrorists were his childhood friends Abdallah and Mourad, since estranged. Lévy wants to understand why they became terrorists, and the terrorists, naturally, want to avoid identification. A sort of detective story ensues, where they negotiate their respective positions with reference to faith, history, family and power. We get to follow both parties in interspersed chapters, adding to the suspense of the narrative. An interesting subplot is that one of the terrorists is a “grand blond” who has a Swedish mother and a Tunisian father, whose aberrant appearance is part of how they can be identified.

It is a story of how we are all human, and that we should be able to live together. Themes from Kayat’s earlier novel la Paria can be discerned, which also deals with the sometimes taut relations between Jews and Arabs – but this time in Paris instead of the Galilee. As with la Paria, the intertwined stories and fates of the characters must be reminiscent of pre-colonial Tunisia were Jews and Muslims lived closer to one another. One can sense that Kayat hearkens back to those days and wants to recall that it is possible to achieve again. Only a writer like Kayat, who is familiar with both of these milieux would be able to write a story like this, and he does it with aplomb. Sometimes it veers into implausible territory (the final journey of Mourad to Stockholm), but then one has to be reminded that it is meant as a parable. La voix du terroriste is a short novel, but it packs a big punch throughout 143 pages, and its message is loud and clear. The absence of a final resolve is surely meant to mirror real life, as if to remind the reader that it is up to us (you and me and everyone else) to change things.

Review of La Voix du terroriste in English by Christophe Prémat

review in French by Albert Bensoussan

My review of Claude Kayat’s La Paria (2019)

House of Glass (Hadley Freeman, 2020)

Longtime journalist at the Guardian Hadley Freeman (since then moved to the Sunday Times) has covered topics of pop culture, politics and feminism. She had the idea to write this book for 20 years, but never knew how to start. She first wanted to write about her grandmother, but then expanded it to include all the siblings, as their stories told a story of the 20th century.

The story revolved around Freeman’s grandmother Sala, and Sala’s three brothers, from Poland to France, and in the case of Sala, on to the US. Freeman herself was born in America and grew up there, until her family moved to the UK when she was 11. It’s a cosmopolitan story, but the transfuge is motivated by oppression. The Glass family are Jews, and a series of pogroms in Chrzanow leads them to decide to emigrate to France in the early 1900s. Thinking they were safe from harm in France, it came as a shock that France became occupied and set up a collaborationist government which persecuted Jews.

It’s a hefty history lesson, with details about the Pétainist leadership. It is also a personal story, about a young girl’s relationship to her grandmother. It’s impressive how well Freeman has been able to weave the story, with an unusual amount of detailed research. Maybe some of it was the result of artistic license? The four Glass siblings all have interesting stories, but the standout is Sander, who reinvents himself as the fashion mogul Alex Maguy in France.

Freeman puts in commentary on political issues throughout the text, in true journalistic fashion, which I believe benefits the text and makes it feel fresh. She also includes her thoughts on Jewish identity and integration. I recently read Anne Berest‘s “La Carte postale” which has a lot of points in common with Freeman’s book. Both are books about discovering a French Jewish family history, by focusing on four different individuals. The writers are also of the same age (Freeman born in 1978, Berest in 1979). Both had relatives who were friends with world class painters like Picasso and Picabia. Both had relatives detained in the French internment camp Pithiviers. They both have also written books about fashion (The Meaning of Sunglasses: A Guide to (Almost) All Things Fashionable; How to be Parisian wherever you are). The difference is in how they chose to write, because Berest wrote in a novelistic style, whereas Freeman chose a journalistic approach.

Mon Amerique commence en Pologne (Leslie Kaplan, 2009)

I was very much drawn to this book, strangely enough solely because of the title alone. I could instantly sympathize with the idea contained within those five words, probably since I too have spent time in three countries (two of them being France and “Amerique”). Poland is not a direct connection, but one set of my grandparents were born just southeast of Poland…

Leslie Kaplan has a trajectory which is somewhat unusual in that her forebears came from Poland, went to America, and then emigrated back across the Atlantic to France, with American confidence and a sense of world-citizenry. Little Leslie was born in the states but grew up in France with a double consciousness, or maybe even triple if one counts the Polish-Jewish roots.

I learn that this is the sixth part of a series of autobiographical writings, and become curious as to what she might have written about in the previous five, because this feels pretty condensed and definitive. It has three parts, childhood, youth and adulthood. These are set in the 50s, 60’s-70’s and 80’s, respectively. The first part meditates on her flailing American identity and how it clashes with her French upbringing. It also tells the story of her parents, who seem to have been career-driven universalists who worked in diplomacy and international relations. Kaplan herself was drawn to the political stirrings that culminated in May ’68 and the second part is rife with stories of that period. She quotes Bob Dylan lyrics, retells her memories of almost all of Jean-Luc Godard films, and other movies of the era. The third part retells the story of a friendship with someone, and feels different, colder and more austere than the previous parts. The 1980s represented a break with the earlier period. I might not seek out more Leslie Kaplan, as it feels like I have got a sense of her style from this book. Maybe later on.